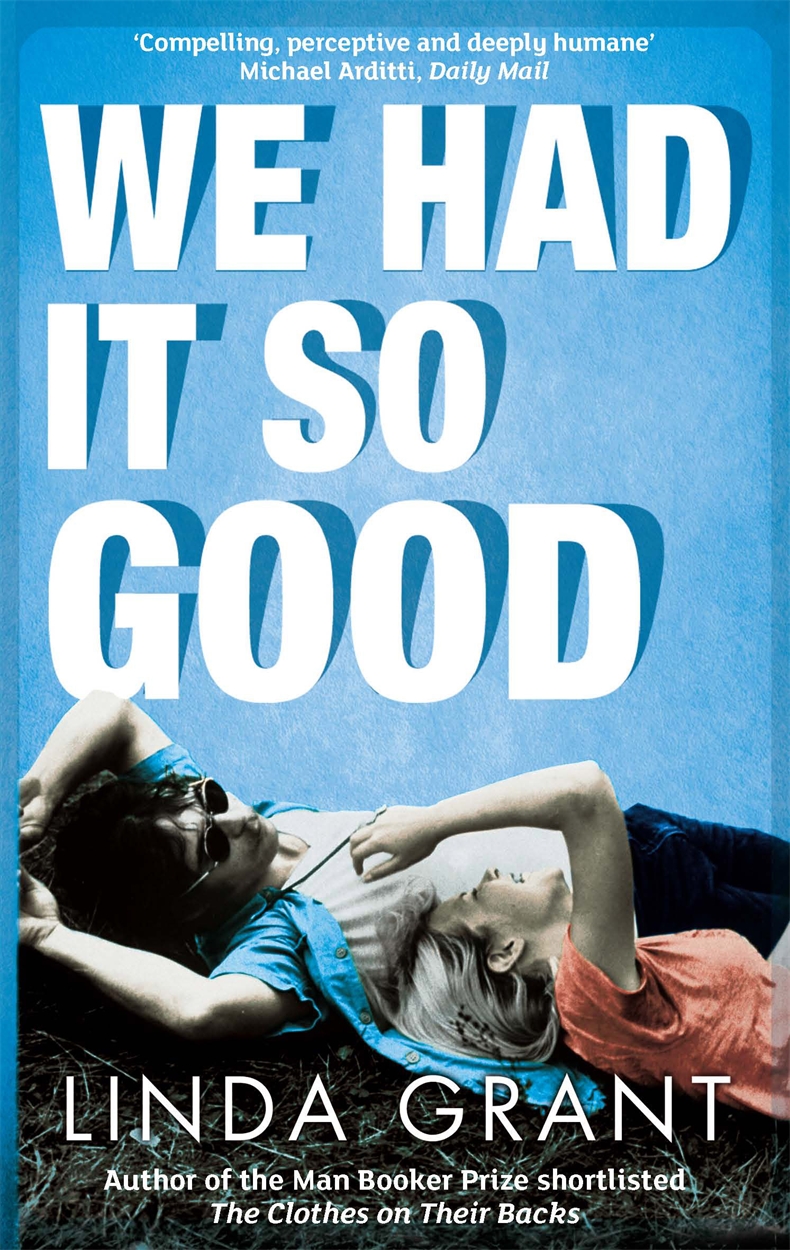

We Had It So Good – Publication Day!

Today sees the publication of Linda’s brand new novel, We Had It So Good. It’s published by Virago and is available in hardback, from all good bookstores and online retailers.

We Had It So Good tells the story of Stephen Newman. In 1968 he arrives in England from California. Sent down from Oxford, he hurriedly marries his English girlfriend Andrea to avoid returning to America and the draft board. Over the next forty years they and their friends build lives of middle-class success until the events of late middle-age and the new century force them to realise that their fortunate generation has always lived in a fool’s paradise.

Here’s a short extract to whet your appetite.

Sunshine

Aged nine, Stephen standing outside the fur-storage depot where his father works, his sturdy legs in shorts planted on Californian ground. Feet wide apart, shoulders up, arms behind his back, his neck sticking out from the collar of a checked shirt to which a narrow bow-tie has been clipped, and his round Charlie Brown head dusted with the dark shadow of a crew-cut. All-American boy.

‘That day,’ he told his children, ‘was the most exciting day of my life. That’s when I put on Marilyn Monroe’s fur stole. And got thumped on the head by my old man when he saw what I was doing.’

The cold-storage warehouse took care of the fur coats of the movie stars. Stephen struggled to express memories he could find no words for, of walking along the lines of minks and sables, ocelots and ermines, allowed to carefully stroke their satin pelts, insert his own small arm into their dangling sleeves and feel the silken linings. His scrubbed hand was permitted briefly to enter the great surprise of a velvet pocket.

‘This coat belongs to Miss Bacall,’ his father told him, in his immigrant accent, ‘this one to Miss Hayworth. The animal was a living thing, a beautiful creature that once was. And only a beautiful woman deserves to wear a coat like this.’

If Marianne and her brother Max, even as children, cynically thought the world of their forefathers was unreal, made up by their father as a bedtime story, Stephen in his time had been far more credulous. For years he had believed that his father was on actual speaking terms with film stars, that he went to work every day with Deborah Kerr and Audrey Hepburn and Ava Gardner. Only after he made the momentous first visit to the cold-storage company, driving home with his father through Los Angeles suburbs, did he learn that the actresses never called to pick up or deposit their own furs: they had assistants to bring in the coats, the heat of the stars’ bodies still trapped in the linings, redolent of their sweat and perfume, the Joy, the No. 5, L’Heure Bleu.

The brutal heavy-set warehousemen regarded the coats as skin, animal pelts, weighty objects to be moved about in freezing conditions. They were all short, tough types, with large forearms and thinning hair. It was a shock, after the feminine world of home, his mother, his two sisters – their hairspray hanging in the air long after they had stood up from the mirror, and face powder leaving scented trails scattered through the house; motes of lily-of-the-valley and lilac whitened the rugs.

Inside the warehouse Stephen listened to his father’s explanations about why a fur needed to be kept under special conditions. The cool air and the darkness stopped the skins drying out, the hairs discolouring and held back the infestation of insects, which could eat away at the garment. The duties of the employees included not just hanging the coats but ensuring that they were not too close together, to prevent crushing. There was regular spraying of the unit with strong chemicals to control pests and rodents. Under no circumstances was a fur to be stored in a plastic bag, which could build up humidity and mould. The sight of a plastic bag in a cold-storage facility was the way, he said, you could detect an outfit run by a crook.

After the lecture, Stephen ran down the racks of furs which hung like heavy headless bodies in the darkness. Doubling back, he came to a rail of stoles that had just arrived for treatment and storage. His father was on the other side of the room smoking the stump of a cigar, his knee raised, his foot resting on a wooden crate, a small, skinny man – with the endurance, his wife said, of an ox – who arrived in America all by himself aged twelve and who barely grew afterwards, as if the soil of home in Europe had given him all the nutrients he needed. She was a head taller than him in her nylons, and her hair rose even higher, blueblack and held up with a butterfly comb.

The garment that lay draped around the hanger was slipping off, and before it reached the floor Stephen raised his arms to catch it. The fur body fell, weirdly, he thought, both heavy and light, and with a fragrance of hot pearls. The hairs brushed his face and tickled him. ‘I had to try that thing on,’ he told his children. ‘I don’t know what came over me, but you know all kids love fancy dress and maybe it was just Hallowe’en come early.’

The weight of the pale mink bore down on his thin arms. He came walking out towards a mirror so he could see what kind of being he had been transformed into. His father turned and saw his only son draped and twirling on his toes in Marilyn Monroe’s champagne-mink stole. Stephen thought he was taking the opportunity to try out transformation. He was exercising his birthright, the American capacity to be reborn.

A hard whack came from behind and he heard his father utter imprecations in his native language, in which there were few vowels and many syllables that seemed to get stuck in the speaker’s throat, choking him.

Born to hardworking immigrant parents in sunny suburban Los Angeles, Stephen Newman never imagined that he would spend his adult life under the grey skies of north London, would marry Andrea for convenience and stay married, and would watch his children grow into people he cannot fathom. Over forty years he and his friends have built lives of comfort and success, until the events of late middle age and the new century force them to realise that they have always existed in a fool's paradise.